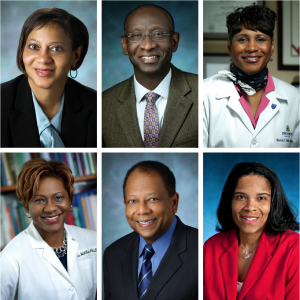

Black history is intertwined in the history of Johns Hopkins with figures like Vivien Thomas, who began as an assistant to Alfred Blalock, being paid as a janitor, and went on to develop procedures used to treat cyanotic heart disease, and Levi Watkins, who became the first black chief resident in cardiac surgery of The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and performed the world’s first implantation of the automatic defibrillator. Today, roughly 29 percent of Johns Hopkins employees are black. Among them are leaders and game changers of our own department such as Bloomberg Distinguished Professors Lisa Cooper and Rexford Ahima, DOM Executive Vice Chair Sherita Golden, American Diabetes Association President for Healthcare and Education Felicia Hill-Briggs, Director of Gastroenterology Anthony Kalloo and Deidra Crews, Associate Vice Chair for Diversity and Inclusion and leader of our Diversity Council. In honor of February’s Black History Month, I’d like to take this time to say how proud and grateful I am of this under-recognized group of individuals who make up our department, our city, and all of Hopkins including, but not limited to faculty, trainees, nurses, administrative staff, security officers, environmental services staff and more.

Black history is intertwined in the history of Johns Hopkins with figures like Vivien Thomas, who began as an assistant to Alfred Blalock, being paid as a janitor, and went on to develop procedures used to treat cyanotic heart disease, and Levi Watkins, who became the first black chief resident in cardiac surgery of The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and performed the world’s first implantation of the automatic defibrillator. Today, roughly 29 percent of Johns Hopkins employees are black. Among them are leaders and game changers of our own department such as Bloomberg Distinguished Professors Lisa Cooper and Rexford Ahima, DOM Executive Vice Chair Sherita Golden, American Diabetes Association President for Healthcare and Education Felicia Hill-Briggs, Director of Gastroenterology Anthony Kalloo and Deidra Crews, Associate Vice Chair for Diversity and Inclusion and leader of our Diversity Council. In honor of February’s Black History Month, I’d like to take this time to say how proud and grateful I am of this under-recognized group of individuals who make up our department, our city, and all of Hopkins including, but not limited to faculty, trainees, nurses, administrative staff, security officers, environmental services staff and more.

In Baltimore City, more than half the population is black (63.3 percent in 2016 according to the U.S. Census) and yet they are treated as a minority and often discriminated against: their hard work goes unrecognized, they’re mistreated by patients and other staff, they suffer the minority tax—being expected to represent/speak for their race—and so on. For this reason, African Americans feel less engaged in entry level positions all the way up through the most senior positions. James Page, vice president and chief diversity officer for JHM, has presented data to prove that an organization that declares diversity and inclusion a priority reap benefits of enhanced engagement, less turnover and higher employee satisfaction not just for African Americans, but across the spectrum.

I think part of honoring Black History Month is noticing those you work with. African Americans uniquely suffer biases, unconscious or not, no matter the level of their positions. Many of these experiences are suffered in private—they occur behind the closed door of an exam room or without drawing the attention of others—and are hard to share with colleagues, much like it is hard for colleagues such as myself to know what it’s like to be a black man or woman. These experiences act as small wounds that can add up and have potential health consequences. There is evidence that these kinds of stresses that are magnified by being a minority can affect not only health but also education, finances, behavior and more. In order to help prevent these consequences, we as individuals need to see beyond our personal space to try to imagine what it’s like to be someone else. We need to encourage others to speak about their experiences. Honoring our diverse history and experiences allows us to improve ourselves for the benefit of all. Both Hopkins and Baltimore are rich, diverse environments that can aid us in building on the core values of diversity and inclusion of all people to launch us into a brighter, more productive and inclusive future.

At times I wonder why it is that people operate with a default focus on differences that appears to underlie sectarianism and conflict. I suspect it has to do with some deeply entrenched tribalism—perhaps part of an evolutionarily curated circuitry, where at one time it may have been beneficial to easily identify individuals as tribe or not tribe. However, as this radar for differences was honed, it is now an obstacle that we must all strive to overcome in order to create a more diverse and harmonious society. My view is that the differences we can readily detect in each other are typically superficial, often failing to reveal core virtues, character or interests. As a result, we must commit to a never-ending journey to raise awareness, and to be open to personal exploration in order to better understand and acknowledge the unconscious biases that plague society as well as ourselves. We must try to work beyond these to assume something grander than the fate of our present society, and, possibly, our own neurobiology. Based on my time at Hopkins, I have many reasons to believe this is possible, and I am fundamentally optimistic about the state of our future. Wishing you a joyous and thoughtful Black History Month.

-Mark